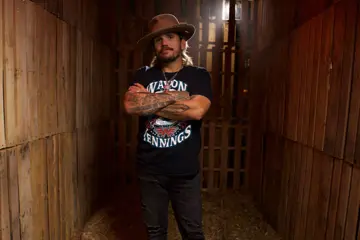

Loren Ryan

Loren RyanCountrytown, in partnership with KIX Country, is proud to announce NSW up-and-comer Loren Ryan as our latest Centre Stage artist. Every fortnight we'll be shining a light on a single artist across all platforms including online features, airplay, and social support.

Zipping around the country making the festival rounds, singer-songwriter Loren Ryan – a proud Gamilaraay woman and winner of the 2023 Toyota Star Maker competition – squeezes several appearances into a short space of time, riding high on the release of her latest single, Take Me Home.

A bright country number doused with pop licks, like much of Ryan’s output, Take Me Home is rife with story – though outside general themes of welcomeness, familiarity and belonging, deeper talks around the song’s origins see Ryan reluctant to discuss. “I’m not really with that person anymore,” she says, very cautiously touching on the track’s romantic connotations. “I was a bit tricked by that person, but still, happy to sing the good song I got out of it!”

A sense of home is prevalent in the single, however it’s one Ryan says she’s left up to interpretation: whatever (or whomever) “home” might mean for the listener is up for them to decide. “Especially when you hear the bridge,” she says, “I wanted to leave it open for all aspects of love. The song went through so many changes. It was a co-write with [producer] Gavin Carfoot – I love working with him, we’re on the same wavelength and influenced by a lot of different styles of music.”

Join our community with our FREE weekly newsletter

From a wider EP due out on January 24, 2024, the overall direction Ryan intends for the release is shaped by the singles’ theme. “I’m working to make all of these songs fit under one title,” Ryan alludes, noting that she can’t yet reveal what her EP is called. “Musically they all include a lot of the things I love – I love country music, the songs are sounding quite pop [and] quite mainstream, but we’re adding elements of musical theatre. Breathtaking moments, moments that move you and prompt a lot feeling.”

And with her old-school R&B vocals, served with a twist of soul, Ryan’s brand of country has created a rather harmonious marriage between two often starkly different genres. “I think they certainly overlap,” she says. “As a singer, I’ve listened to a lot of different music, I’ve really worked on my voice. It does sound soulful, [but] I wouldn’t say it’s too far from country. I’m not doing anything that Carrie Underwood can’t do, not doing anything Bella MacKenzie can’t do.”

Those familiar with Ryan’s output will know that, of course, she is doing things very differently from either of those cited contemporaries. And for those unfamiliar, Ryan not only sings in a combination of Australian English and Language, but she peppers her music with cultural heritage by extension of her work as an Aboriginal Culture teacher – completely unique to anything Carrie Underwood does. “Growing up, we didn’t have a lot of Language,” Ryan begins, “so to have this missing element of my culture and my identity, left a really big gap when it comes to understanding who I am, and feeling like a complete person.

A sense of poignancy cloaks Ryan, as she carefully chooses the words to share the story that has, in many ways, helped shape her career. “When my parents were growing up,” she says, “Language was forbidden to speak. You’d get punished.” While her parents were subject to curfew, Ryan explains that her great-grandmother grew up in a time where she was made to sign an exemption form to leave the mission, stipulating you weren’t “going to socialise with Blakfellas”, and that you were going to assimilate into White culture. “There’s a publication on her, when she did sign it; they had magazines that were propaganda they’d send to all the Missions. Basically they said, ‘Look at all these good Aboriginal people who are assimilating, you should strive to be like them.’”

When people like Ryan have stories like your local mob, it’s hard not to sit back in disbelief and consider this was a country-wide issue. “They were pushed out to campgrounds just outside of town on the levy bank, and they built their house out of scraps from the tip. Dirt floors, tin shacks. That’s it. My mum was eight years old before they lived in a real house. Even then it was traumatic to live in town, such bad, bad, bad things happened.”

Motivated by her family’s enforced disconnect with their culture, Ryan is proud of where she comes from, wanting to learn more about her heritage and culture, going so far as to study and learn in her own time at school when formal lessons or discussions were absent. She says, “The difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people when it comes to what with we do our lives, you can choose what your legacy may be, but if you’re Indigenous, you just have a responsibility to do these things.”

In 2019, Ryan said, “When it comes to identity, knowledge is power.” In saying that, by arming Indigenous people with knowledge of their culture and heritage, Ryan could be levelling the playing field. “I quickly figured out that if I didn’t take it upon myself to learn these things, they’d be lost forever. And I didn’t want them to be lost with my generation. I sought out knowledge and knowledge holders, spending a lot of time with Elders. I spent a lot of my time with aunties and uncles who knew Language and culture.”

Ryan explains that developing a confidence in using music as her focal platform to share not only her personal experiences, but her cultural heritage was a strategic move. “I knew I could reach more people through music,” she says, “and so I would teach through music to fast-track the revival of the Language. I really wanted more people to know more language because it was dying. The man who taught me Language passed away not long after I graduated high school.

“I learned that music is an easy way to teach people, and a fast way to get it out there. It was not to establish myself as someone who just sings in language, I did because I wanted other people to learn.

When she thinks about her music, Ryan can’t attest to being firstly a country musician, or a culture teacher in music – it’s neither first. “My very first performance was a country song in Language with country music’s living legend – who doesn’t get their flowers often enough, I feel – Roger Knox.

“For me, it feels seamless, the combination. When it comes to country music and First Nations peoples, country music ties itself onto storytelling and humility, and that’s the foundation of it, whereas First Nations peoples have told their stories through song and dance for thousands and thousands of years. Both coexist as basically very similar things. They go together. I like painting things so it’s not us and them, that’s why I say things the way I do.”