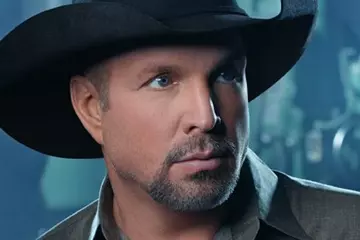

The Saints

The SaintsAustralian producer and guitarist Mark Moffatt died on Friday, September 6, 2024, at age 74, in Nashville, Tennessee, after devoting his life to music. He had battled pancreatic cancer for more than a year.

He produced more tracks in the APRA Top 30 songs of all time than any other producer and worked with an incredible fifteen ARIA Hall of Fame nominees.

Moffatt relocated to Nashville in 1996, devoting his life to bridging the international divide, serving as the Americana Music Association’s president and becoming a mentor and guide for countless Australians looking to impact in the world’s country music capital. He also served as APRA’s Nashville Ambassador for ten years and was awarded the CMA Global Achievement Award for his efforts. At the time of his passing, he was working on a new project Kilo with John Swan, which The Music profiled last year.

As much as Moffatt loved his music, his first love was his family. He is survived by his wife, Lindsey, stepdaughter Dana, two granddaughters—the loves of his life—his son Geordie, and extended family in Australia.

Mark Moffatt’s Incredible Musical Journey

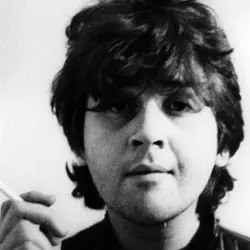

Mark Moffatt remembers it was a Tuesday night. After returning home following a stint in London, the young record producer was working at his mate Bruce Window’s recording studio in West End, on the south side of the Brisbane River. They didn’t get to record many rock bands; the studio’s core business was commercial jingles.

But one afternoon, a drummer and bass player turned up in their transit van and said, “We’d like to make a record.”

Join our community with our FREE weekly newsletter

When they started playing on that fateful night, Moffatt felt that the guitarist’s amp wasn’t up to the job. So he plugged in his own Fender Super 60 and turned it up to 10. “And suddenly, bang!”

The 16-track studio had a concrete hallway, which made the record sound even angrier and louder.

The next day, Moffatt mixed the single and the B-side. The whole session cost $170.

Three months later, the single was making headlines in the UK: “Sounds’ Single of This and Every Week”.

“You like Quo or the Ramones?” the reviewer asked. “This pounds them into the dirt. Hear it once, and you’ll never forget it.”

“There was a sense that something had fallen into place,” Moffatt recalls. “It was like Sun Studio and Elvis Presley. That, to me, was a happy accident. Elvis just turned up, and then, boom.

“I’m really thankful that I had one of those in my life. The stars aligned, and I’m glad it was in Brisbane.”

Mark Moffatt is a proud Queenslander. He grew up in Maryborough. “But I left home pretty early because there was not much happening musically in Maryborough.” After discovering The Beatles, he moved to Bundaberg, where there was a thriving scene. “There were a lot of British migrants – it was always the way in Australia: wherever there were Poms, there was music.”

He lived at a boarding house run by an English family whose 19-year-old daughter had every Stones record. Then Moffatt landed in the big smoke of Brisbane, where the blues scene blew his mind.

“The Brisbane blues,” he smiles, “It’s undeniable.”

Moffatt traces it back to Mick Hadley and The Purple Hearts. Hadley had moved to Brisbane from the UK in the early ’60s. “He’d seen Alexis Korner and Graham Bond and the whole thing,” Moffatt explains. “Lobby [Loyde] was playing surf music until he heard Mick Hadley’s record collection.”

The young musician loved the energy of the burgeoning Brisbane blues scene, which included The Purple Hearts, Bay City Union, Thursday’s Children, and early Chain. Years later, Brian Cadd told Moffatt that The Purple Hearts scared people in Melbourne because they were so aggressive.

But Brisbane at the time was not big enough for a man of Mark Moffatt’s talents. “Brisbane was tough because it was nowhere,” he says. “It was punching way above its weight, but it was not part of the industry like it is now.”

So, Moffatt jumped on a boat and headed to London in 1972.

“All I’d ever done was play guitar and work at a music shop, Drouyn Drums, selling Australian-made drums,” he remembers. So, when he landed in London, Moffatt wrote to every guitar shop listed at the back of Melody Maker. He received two replies: one from a classical store and another from a shop on Denmark Street called Top Gear.

In his second week at Top Gear, Jimmy Page walked in. Moffatt got to know the regulars, including Paul McCartney and Gary Moore, and he would often play sessions at the local studios, where he would bug the engineers, asking: “What does that button do?”

“By the time I got back to Brisbane, I knew enough to blag my way into Bruce’s studio.”

Moffatt’s dream was to turn Brisbane into Muscle Shoals. “What a pipe dream that was,” he smiles.

He joined the Carol Lloyd Band, playing guitar and pedal steel. “We were signed to EMI and did an album [Mother Was Asleep At The Time], but with the cost and the isolation, it was very tough to do anything from Brisbane. It was just dispiriting.”

After the success of The Saints, EMI asked Moffatt if he’d go to Melbourne to produce the outlaw country band Saltbush. He landed at TCS studios at Channel Nine, where the studio manager, Barry Coburn, offered him a job, and Moffatt found himself working alongside the noted engineer John French. “I was still pretty green, and John rounded that out,” Moffatt says. “He never actually said, ‘Here’s how you do it’; it was just being around him and learning. He was an amazing guy, an amazing engineer.”

After a stint at TCS, Moffatt relocated to Sydney, where he became Festival’s in-house producer and worked on some of the biggest Australian records of the ’80s and early ’90s. Then, in the mid-’90s, he got another call from Barry Coburn, who was now offering him a job in Nashville.

Since 1996, Moffatt has been based in Nashville, where he has helped countless Aussie acts, including Keith Urban and O’Shea, as well as making albums with Ross Wilson, Richard Clapton and Brian Cadd.

And he’s still making music – check out his killer project with Swanee, Kilo Band, a blazing, bluesy ball of energy that is a nod to Moffatt’s formative years in the Brisbane blues scene.

Mark Moffatt is an unsung hero of Australian music. You might not necessarily know his name, but you’ll definitely know his work.

The Music sat down with Moffatt to chat about some of his greatest hits.

The Saints – (I’m) Stranded & No Time

There was something serendipitous about that Tuesday night in Brisbane. As Ed Kuepper would note, The Saints were lucky that Mark Moffatt was in the producer’s chair that night “and not some drone”.

“I’d seen the New York Dolls,” Moffatt says, “and I’d been around the early British pub rock scene with Ducks Deluxe and Brinsley Schwarz. It all made sense to me, which is why I didn’t dismiss these guys as just a bunch of noise.”

Moffatt also loves No Time, which was the B-side of (I’m) Stranded. “That even rocked a bit harder. Ed’s guitar playing in that was just so great.”

The Monitors – Singing In The 80s

“While working at Festival, when there was not much going on at the studio, I’d be banging away at my own ideas. One of my jingle partners in Brisbane was Terry McCarthy, who was the creative director at a big agency. I sent a cassette to him, and he wrote some lyrics on the plane on the way down to Sydney.”

That became the Top 20 hit Singing In The 80s, with the female vocal by Kim Durant (performed in the video by the Blakeney twins, Gillian and Gayle).

“I threw it into the selection meeting at the Festival boardroom, and next thing they put it out, and it sold 50,000 records … I still get royalties from around the world.”

The Monitors were dubbed “the Aussie Buggles”. “It was very much inspired by Trevor Horn,” Moffatt says.

Mondo Rock – Chemistry

“I was really a nobody, and I’m not a networker. I was just a kid who wanted to learn how to be in a recording studio. The Monitors thing happened, and this is how I think I ended up producing Mondo Rock’s Chemistry album …

“The voice of Countdown was another Brisbane boy, Gavin Wood. On one episode, he gave me three namechecks: ‘Good mate from Brisbane …’ He didn’t say that, but that’s essentially what he was saying. And not long after that, I got a call from Ross.

“That was awe-inspiring and a little intimidating – it was Ross Wilson! I learned a lot from him, particularly about the groove element and editing tracks together, stuff I’d never paid much attention to. He would pull everything apart and really go for the groove. Chemistry was a combination of Ross’s approach and my affinity with guitar sounds and amps. Eric [McCusker] got some great guitar sounds on that record.”

Chemistry was Mark Moffatt’s first platinum record.

Pat Wilson – Bop Girl

“Chemistry worked out so well; Ross called me to work on Bop Girl.

“During that early 80s period when I was working at Festival, a guy called Ricky Fataar had just moved to Australia. He’d played on Renée Geyer’s So Lucky album, but I have to admit I didn’t know who he was – I had no idea he’d been a part of The Beach Boys and The Rutles.

“But we started hanging out together and became a production duo. And we worked on Bop Girl.

“To be honest, it was kind of daunting because Hanna [Ross Hannaford] had done the demo. I basically had to reproduce his parts – and I play nothing like him … who did?

“It took a while to do that record, and it was hard to tell what would happen with that track if Pat was going to work as an artist. But she certainly did.”

And a 16-year-old Nicole Kidman made her screen debut in the Bop Girl video.

Tim Finn – Fraction Too Much Friction

“I worked on a movie called Starstruck that David Elfick produced. I put the tracks together, and one of them was Body And Soul, which Tim Finn wrote. Tim then wanted to make a solo record.

“He basically came into the studio with a notebook filled with a bunch of songs. He played them all on piano or guitar, and that night, we all took home a cassette and picked out 15 songs, and then we came in and started recording them.

“There was no preamble; nothing was preconceived. It was just a great artist who was feeling how fresh it all was for him.

“And Ricky Fataar is something else – he’s way more than a drummer. A lot of music flows through that guy, and he can pull stuff out of people. In those sessions, you could tell something was going on. It was just so smooth; I think we had it done in like two weeks.

“I felt a bit of antipathy from the rest of the band [Split Enz]. I think they felt it broke the band up. But it was a very inspiring and stimulating time for Tim. There was stuff happening.”

Jenny Morris – You I Know

“You I Know was two parts of a Neil Finn song. He brought two tapes in: one had the verses, [and] the other contained the choruses. And we put those two pieces together.

“I remember Neil said, ‘This is going to be a hit because it’s got you and I in the title.’

“I’m surprised this song hasn’t been recut because it’s got all the hallmarks of a Neil Finn song. All the stuff it takes to make it work.”

Paul Norton – Stuck On You

“After the Tim Finn album, Nathan Brenner [Tim’s then manager and Michael Gudinski’s archrival] approached me about starting a label. Blithely – again not being hip to industry politics – I said, ‘Yeah, sure.’

“The label was called Centre Records. We did a Stephen Cummings record [This Wonderful Life] and a few other things. I walked out of EMI one day and bumped into Gudinski. He said, ‘You’ll never work for me again.’

“Then, one day, Gary Ashley [Mushroom GM] called and said, ‘All is forgiven, we’ve got this guy, Paul Norton … I’m going to send you a tape.’

“I flew to Melbourne and made the record. It was very carefully crafted. Wendy [Stapleton] had a lot to do with that, with the backing vocals. And I love the pedal steel solo by Garrett Costigan.

“They went to England and made the rest of the album. It didn’t sound as rootsy, which was a bit disappointing. But Stuck On You was a big hit, and I think it stands up pretty well.”

Yothu Yindi – Treaty

“This was life-changing, really.

“I’d made an album with Shane Howard, River, which is a great record. Dr Yunupingu heard it and told Michael [Gudinski]: ‘We want the guy who produced that record.’

“I spent time with the band and learned their tribal beliefs.

“The didge player, Milkay, was unbelievable. He was like the master. The middle break in the original version, with Ricky [Fataar] playing kick drum and hi-hat and Milkay playing the didge … everyone just went crazy in the control room, jumping up and down.

“I was also really thrilled with the [Filthy Lucre] remix. They did a great job.

“I remember when Treaty was out, and we were still working on the album, I was with the band at Tullamarine airport, and these white schoolkids came running up to these Aboriginal guys to ask for their autographs. That was a very special moment.”

Anne Kirkpatrick – Out Of The Blue

“Rod Coe, who was Slim and Anne Kirkpatrick’s producer, thought that Anne would benefit from working with another producer. I’m so proud of the records I made with her, particularly Out Of The Blue, which won an ARIA and opened the door for a lot of contemporary country stuff and Americana in Australia. Kasey Chambers and many other artists walked through the door that Anne opened.”

And a couple from left field …

Audio Murphy Inc. – Tighten Up Your Pants

“As a producer, I always had ideas. In 1994, I decided to do a techno-yodelling track with Mary Schneider. She turned up with her daughter, Melinda, who’s a great singer. I put that out and called it Audio Murphy.” It became a Top 40 hit.

Slim Dusty – Fiddler Man

This is a rarity – a Slim Dusty dance track. “It shocked a lot of people,” Moffatt admits. “But Slim loved it – he was always up for different stuff. I dug out an old Saltbush song called Fiddler Man, and we remade it as a dance track.”